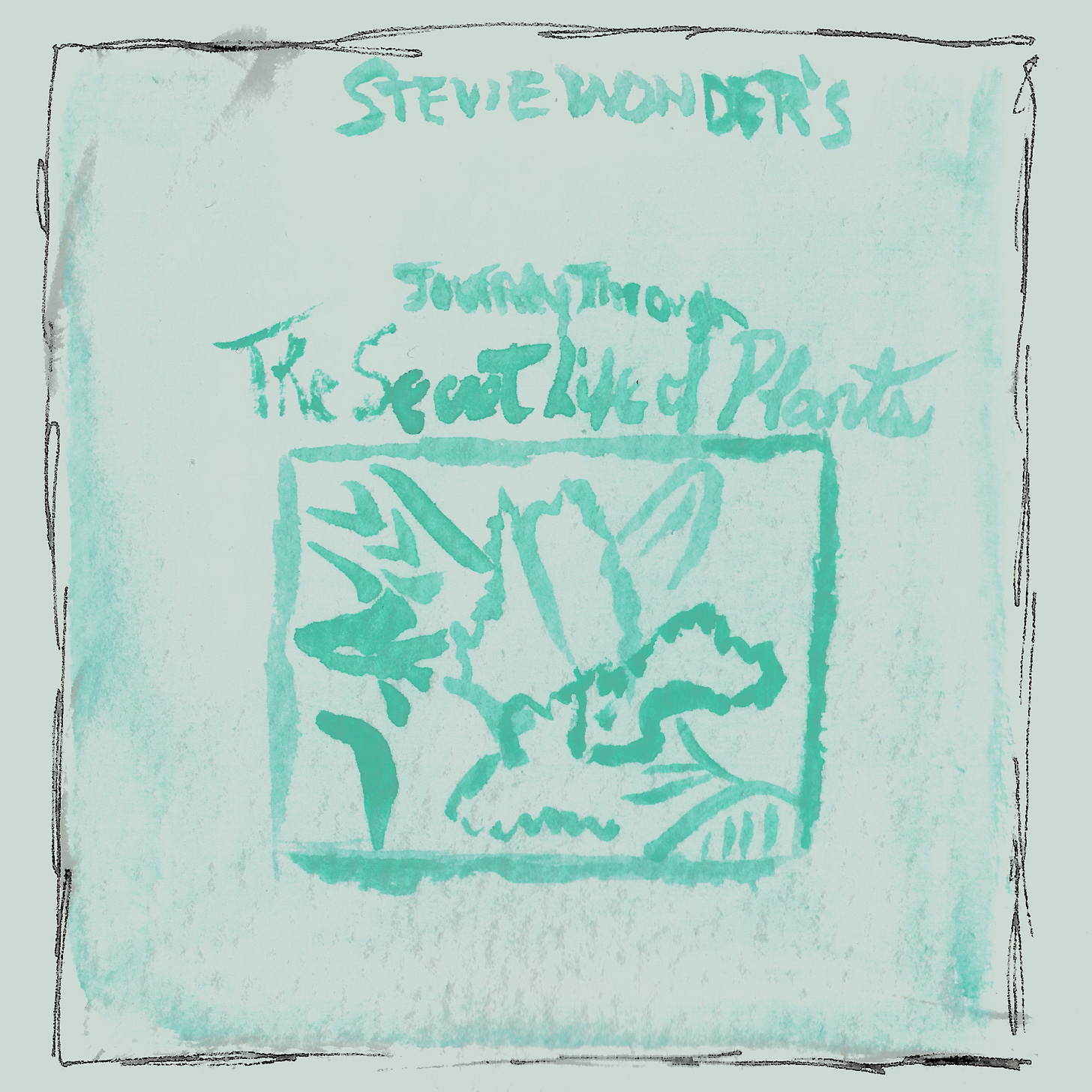

Stevie Wonder's Journey Through "The Secret Life of Plants"

Stevie Wonder; "Send One Your Love"; from an estate sale

As we know, Stevie Wonder released Songs in the Key of Life in 1976, a sprawling double album that served as both a culmination and celebration of his unparalleled run through the early '70s. It was deeply human, richly orchestrated, and brimming with joy, pain, protest, and praise—all of the complexity of life. Just three years later, Wonder took an unexpected turn with his soundtrack for a nature documentary, one few people had seen. Since he was scoring it, he had to have each frame meticulously and mathematically described to him to precisely replicate the on-screen action.

On the surface, it seemed like a retreat from the political immediacy and accessible soul of his previous work. He went from the biggest album of his career to songs like this? Is this another Sly Stone situation? What gives? In reality, it was a leap forward—into technology, ekphrasis, and a kind of ecological spirituality.

So many times, people view urban life as a counterpoint to the pastoral—trusses and concrete versus tree canopies. The music of Motown, of the Motor City, chugging off the assembly line and into the grooves of a record is distinctly different from someone in a holler in West Virginia plucking a passed-down high and lonesome sound on their heirloom banjo. One is polished, smooth, crafted for mass culture; the other bespoke, with rough edges, truly unique.

But Journey Through resists that tidy division. In fact, it finds common ground between the synthetic and the organic. Journey Through proposes that plants are not mute decorations or resources to be extracted—they are sentient, communicative beings with their own presence, their own way of influencing the course of events and acting on the world. The record blurs the binary, and reminds us that—in some instances—technology can help us commune with the Earth just as much as it sets us apart from it.

The album elevates its quiet wisdom through electronic tone poems and textures that feel less like songs and more like conversations with root systems and sunlight. It was an imagined world crafted from an emergent digital utopia, where any waveform could be replicated in the box, used to conjure complex arrangements that mimic the inner life of plants.

Despite that so few people listened to this music when it came out, this shift marked a pivotal moment in Wonder’s career: from master songwriter to sonic gardener. He had experience setting the timbre and tone of his performances, but mostly worked with outside producers on some of his earlier albums. On this one, Stevie played virtually all the instruments himself. Whether it was the groundbreaking digital Computer Music Melodian, the Yamaha GX-1 synthesizer, Moog synths, or electric pianos, he precisely programmed and shaped complex synthesizer patches, adjusting filters, envelopes, and pitch bends in real time to breathe life into synthetic textures. Wonder wasn’t following trends—he was listening to the roots, to the soil, to something deeper.

I remember the first time I listened to Journey Through on my iPod, working quietly in my mother’s garden to prune and shear off some of the thorns, making it easier to pick berries. The late afternoon light was soft and warm, and all around me ivy slowly crept over old garden tools, rusting in place from last season. The raspberry vines were climbing over the fenceposts that separated our yard from the neighbors. It felt like time had softened here, that the world was gently folding in on itself, wrapping and enmeshed. Occasionally some tendril would reach out and rip out my headphones, as if to remind me that I should be listening to the plants right in front of me, instead of someone else’s.

Verdict: Keep

How did that flower eat the bug, Daddy?