The year this album came out I missed seeing Justin Vernon and the rest of the group at a local venue on my college campus. Unlike with Radiohead, I wasn’t willing to sacrifice my grades for a band I didn’t yet know well—despite their growing reputation as indie rock darlings, bolstered by Pitchfork and other independent media outlets. Pitchfork was inching toward its poptimist era, and I was starting to grow skeptical of their endorsements. Still, Skinny Love was undeniably good—and remains so, all those years later.

While I didn’t outright lie in my previous post about only doing one solo concert, when I played music with friends, I was known to perform a couple of solo songs. It was strictly in my capacity as a side man, filling time in the setlist. Once, in the affluent suburbs of the city near my hometown, I tagged along with D and his partner N, playing with them as a sort of hired gun at a function to celebrate someone’s graduation. We rehearsed one of D's originals loosely, N sang lead on another, and I added high harmonies in falsetto. I performed Diamonds and Gold under a tree next to a hammock while they took a break. We followed it with an acoustic rendition of OutKast’s Hey Ya—as was the custom back then—before launching into Flume from this record.

I got some hors d’oeuvres out of the deal, and a nice conversation with a zoology grad student who visited Mozambique. She suggested that sometimes she was happy to have studied rare species, because she had an excuse to drop out and run away.

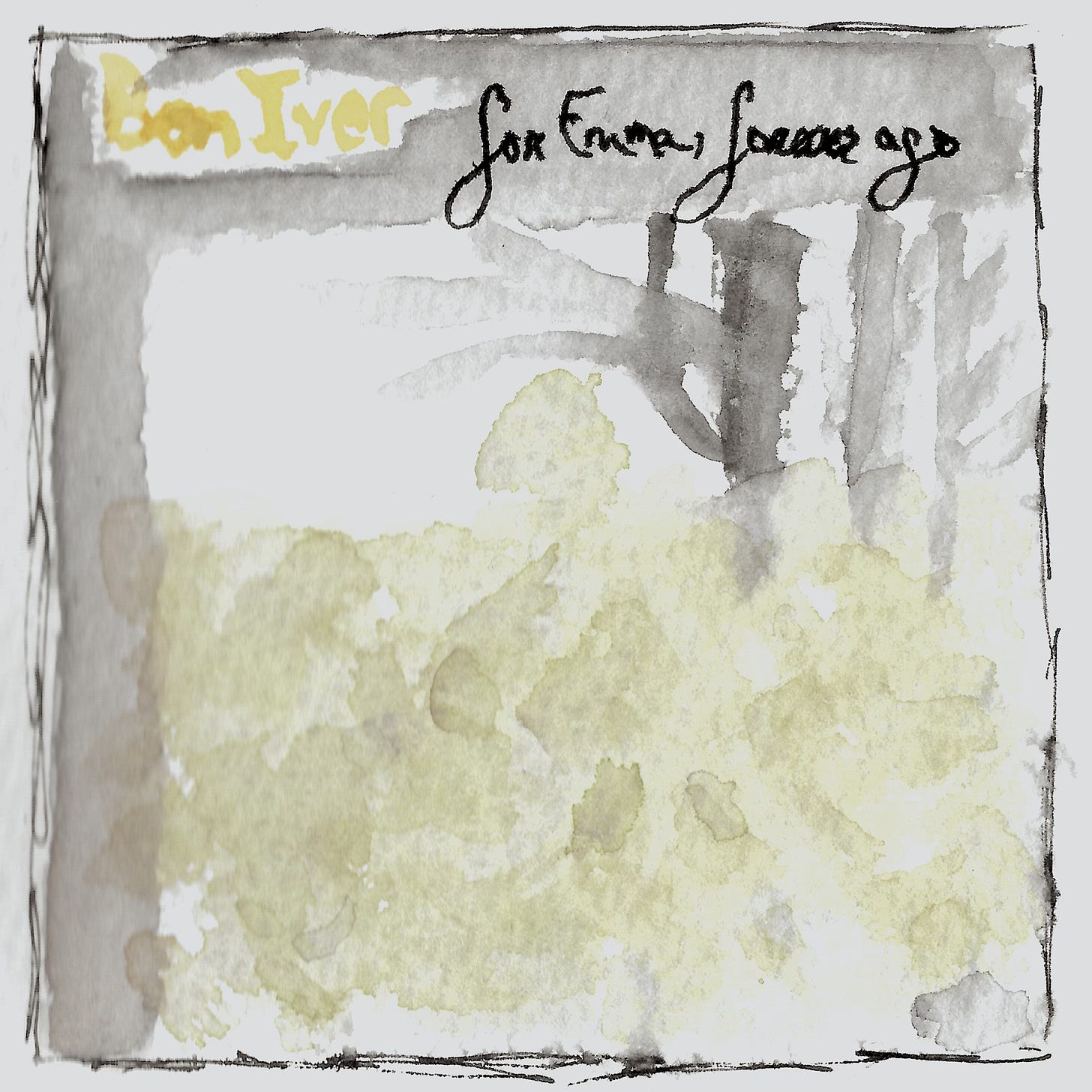

And that's not dissimilar from how the media latched onto and spun the Bon Iver story. At the time, reviews fixated on the mythos: Justin retreating to his family’s cabin to recover from illness and heartbreak, channeling it all into a cathartic song cycle. But that narrative of escapism and pastoralist writing overshadowed what made the record truly remarkable: its experimentalism, its gentle electronic textures, and its bold vocal layering.

The autotune on The Wolves (Act I and II) presaged a rapid and unexpected ascent to fame that would eventually intersect with the hip-hop world. The lyrics throughout often feel less like deliberate lines and more like sound poetry—meaningful, maybe, but also mysterious, fragmented, more vibration than message; kind of like clanging instead of through-composed ideas. The ambience of the EBow on the resonator guitar’s strings, close-miked with a SM-57 makes the entire thing sound as if it’s happening right in front of you.

But Flume captures all of these ideas so perfectly, especially in the chorus—several listens through, semantic satiation does its work and you’re left with a collection of undulating vowel sounds and ululations, not unlike how it happens on Rhinestone Cowboy. Wrapped up in sound; a blanket of harmonies to help you get through the winter.

Though the media cast him as a broken man in exile, I don’t think Justin was exactly down and out. He seemed more like someone searching—for a new voice, a new self, after losing his best friends and his high school band in North Carolina. At this point, no one knows how “bon hiver” becomes “Bon Iver,” not even the man himself. This is where the story begins.

Verdict: Keep

Are you holding all the tickets, or are you holding all the fines?